New research suggests that "little red dots" seen in the early universe may actually be a new class of cosmic object: black hole stars. If this theory is correct, it could explain how black holes managed to grow to supermassive sizes before the universe was even 1 billion years old.

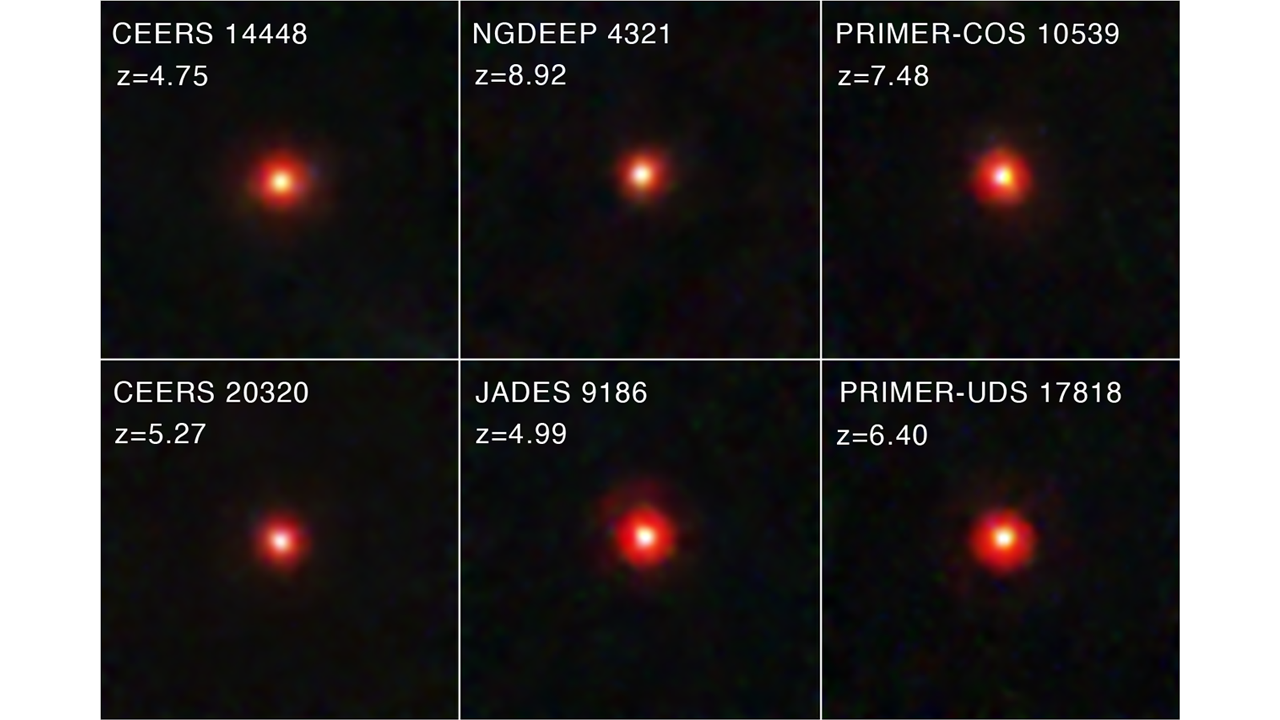

Little red dots are one of the most curious celestial objects viewed thus far by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Astronomers theorize that they are early galaxies that existed earlier than 700 million years after the Big Bang, that are unlike anything seen in the local and "modern" 13.8 billion-year-old universe.

If they are galaxies, these little red dots are surprisingly mature and well-developed for galaxies that exist so soon after the Big Bang, packed with aging and cold red stars. In fact, the concept is so troubling to scientists that some have dubbed little red dots "universe breakers" as they challenge what we thought we knew about galaxy formation and cosmic evolution. This new research, however, could apply some superglue to our broken theories by suggesting a new identity for little red dots and an entirely new class of cosmic object.

Performing an analysis of the little red dots, the researchers suggested that, rather than being ancient, well-developed galaxies, little red dots may be vast spheres of dense and hot gas that look like the atmospheres of stars. However, rather than being powered by nuclear fusion, like stars are, the engines of these objects are supermassive black holes greedily feeding on surrounding matter and blasting out energy.

"Basically, we looked at enough red dots until we saw one that had so much atmosphere that it couldn't be explained as typical stars we'd expect from a galaxy," team member and Penn State University researcher Joel Leja said in a statement. "It's an elegant answer, really, because we thought it was a tiny galaxy full of many separate cold stars, but it's actually, effectively, one gigantic, very cold star."

The theory could explain why little red dots appear more massive and much brighter than galaxy formation models suggest. To be so bright, a galaxy would have to be loaded with stars at an impossible density.

"The night sky of such a galaxy would be dazzlingly bright," Princeton University researcher Bingjie Wang said. "If this interpretation holds, it implies that stars formed through extraordinary processes that have never been observed before."

Little red dot theories fall off 'the Cliff'

Initially believing little red dots are ancient galaxies, Leja and colleagues examined light from these objects at different wavelengths, or spectra, throughout 2024. In July of that year, this investigation led to the discovery of an early and large object, which they nicknamed "the Cliff."

The team realized that the Cliff, located around 12 billion light-years from Earth, is exactly the sort of object they needed to investigate the nature of the JWST's little red dots.

"The extreme properties of The Cliff forced us to go back to the drawing board and come up with entirely new models," team member and Max Planck Institute for Astronomy researcher Ann de Graaff said in a separate statement.

The spectra of the Cliff indicated that it is coming from a single object, not a wealth of densely packed stars. In fact, it appears to be the result of a supermassive black hole that is feeding so voraciously that it is cocooned by a fiery sphere of gas.

Though supermassive black holes sit at the heart of all large galaxies, and some are indeed feeding, scientists aren't exactly sure how they reached masses equivalent to millions or even billions of suns. This is especially perplexing when supermassive black holes are seen in a time when the universe was less than 1 billion years old.

That's because the merger chains of subsequently larger and larger black holes that are thought to create supermassive black holes should take longer than 1 billion years, even if this growth is supported by the accretion of matter by the black holes involved.

The mass increase of feeding black holes like the one seen as the Cliff is "turbo-charged," meaning these new black hole stars could help to explain the growth of supermassive black holes.

"No one's ever really known why or where these gigantic black holes at the center of galaxies come from," said Leja. "These black hole stars might be the first phase of formation for the black holes that we see in galaxies today — supermassive black holes in their little infancy stage."

The JWST is sure to continue to investigate little red dots in the early universe to get to the bottom of their true nature, but the team thinks their theory is the one that best fits the current picture of these perplexing objects.

"This is the best idea we have and really the first one that fits nearly all of the data, so now we need to flesh it out more," Leja said. "It's okay to be wrong. The universe is much weirder than we can imagine, and all we can do is follow its clues. There are still big surprises out there for us."

The team's research was published on Wednesday (Sept. 10) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments